Antibody testing has been in the news quite a bit lately, says Marla Ahlgrimm. But what is it? And is it a good indicator of whether or not a person is immune from the coronavirus disease?

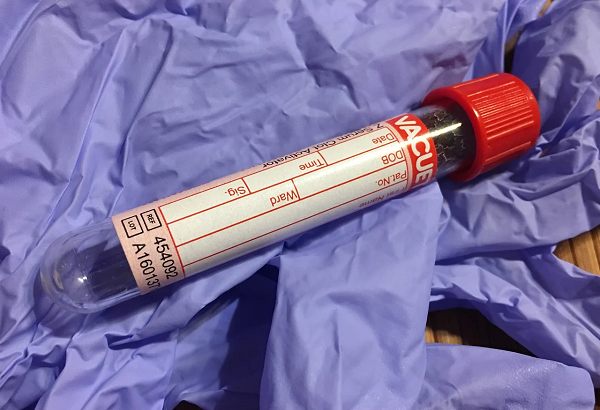

For the last several weeks, people who believe they’ve been exposed to or have had the coronavirus have been flocking to healthcare offices and pharmacies for the newly-available antibody test. According to Marla Ahlgrimm, this is simply a blood screening that can determine who has been exposed and, hopefully, who has immunity from COVID-19.

The retired pharmacist cautions, however, that despite widespread availability, the test may not be perfect. Since the virus is novel, or new, researchers have not yet pinpointed every potential immunity signal. Scientists also do not know how long immunity will last. One thing that is known is that most viruses, including others in the coronavirus family, leave the infected protected from subsequent exposure.

One of the biggest problems with testing, however, says Marla Ahlgrimm, is that many policymakers are making important decisions based on the hope that some are immune. In some areas, employers are requiring immunity certificates before allowing individuals to return to work without restrictions.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, a familiar face in the news since March, explains that limited data means that experts have to use historical evidence to make decisions. As the head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the respected physician has publicly stated his position for months. The World Health Organization seems a bit less enthusiastic about immunity testing. The WHO asserts that it would like longer-lasting results before getting too excited.

According to Marla Ahlgrimm, antibody testing is accurate for most diseases. And, as more and more people are tested, the hope is that the United States can go back to normal. Unfortunately, because there are so many manufacturers of the test, results can vary wildly. Marla Ahlgrimm points out that no test is 100% accurate, but says that lack of regulation and an even lesser understanding of the virus means that some may be grossly inaccurate.

A significant problem with any antibody testing is a false reading. Marla Ahlgrimm says this can happen when the test mistakes one marker for an antibody or misses markers completely. The United Kingdom has already run into this problem, and lawmakers there have slowed the use of antibody testing because of accuracy discrepancies.

Marla Ahlgrimm points out that detecting antibodies is just a first step. But, for the general public, knowing there is an immunity may ease some fears. She cautions that people should understand what immunity means. In this case, it does not mean that a person cannot get the virus, only that the immune system essentially wipes it out before it has a chance to gain a foothold. People who have developed antibodies to the coronavirus are also unlikely to spread it to others, meaning these individuals would be considered safe to be in public spaces without a facial covering.

Marla Ahlgrimm points out that detecting antibodies is just a first step. But, for the general public, knowing there is an immunity may ease some fears. She cautions that people should understand what immunity means. In this case, it does not mean that a person cannot get the virus, only that the immune system essentially wipes it out before it has a chance to gain a foothold. People who have developed antibodies to the coronavirus are also unlikely to spread it to others, meaning these individuals would be considered safe to be in public spaces without a facial covering.

Marla Ahlgrimm says that only time will tell how accurate antibody testing is or is not. In the meantime, she recommends that everyone practice safe social distancing and, more importantly, wash their hands and stay home when they are sick.

Marla Ahlgrimm has co-authored two ground-breaking books,

Marla Ahlgrimm has co-authored two ground-breaking books,